The ancient Maya, whose civilization flourished

and fell centuries before the arrival of the Spanish to the Americas, were literate and had an advanced writing system which they used in books, paintings and stonecarvings. When the descendants of this mighty civilization were

conquered by the Spanish in the early 16th century, they still had thousands of books, elaborately painted with symbols and images. Unfortunately, only

four of these books survived the bonfires of the zealous priests. One of the surviving codices (a Maya book is called a codex) is the Paris Codex, which deals with astronomy and rituals.

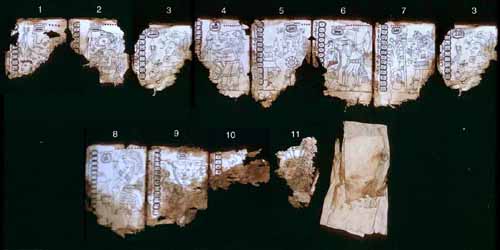

The Paris Codex is believed to be a fragment of a larger document, broken at some unknown point in the distant past. Only eleven pages remain: they are painted on both sides. The thick “paper” is the inner bark of a fig tree. The pages are approximately 23.5 cm. high and 12.5 cm. wide. When folded out, the codex is 1.4 meters long. The pages contain a series of colorful glyphs and images: it is obvious at a glance that different scribe/artists worked on the Paris codex. The codex is in bad shape, badly battered, stained and faded: whole sections have unfortunately been erased by time and wear.

The document is in such bad shape that researchers have been unable to use part of it for carbon dating, leaving only clues within the text itself for determining its place and date of origin. Sylvanus Morley, one of the top Maya scholars, associated the text with the Maya city of Mayapan based on similarities between the document and a certain stela at Mayapan. The date associated with these glyphs can be interpreted as a number of dates from 928 to 1697 A.D., but evidence seems to indicate it was written around 1450 A.D. This would seem to be supported by part of the text, which describes certain cycles between 1244 and 1500 A.D. Some recent researchers believe the text was created earlier than 1450 A.D., perhaps as early as 1185 A.D.

The Paris Codex was acquired by the Paris library in 1832: its movements before that date are a complete mystery. There are some notes written in Latin in the margins of some of the pages, but no one knows who wrote them and they do not shed any light on the origins or history of the codex. The Codex made a narrow escape at one point: apparently it was found in a bin next to a fireplace in the library in 1859. The original is still at the Paris Library.

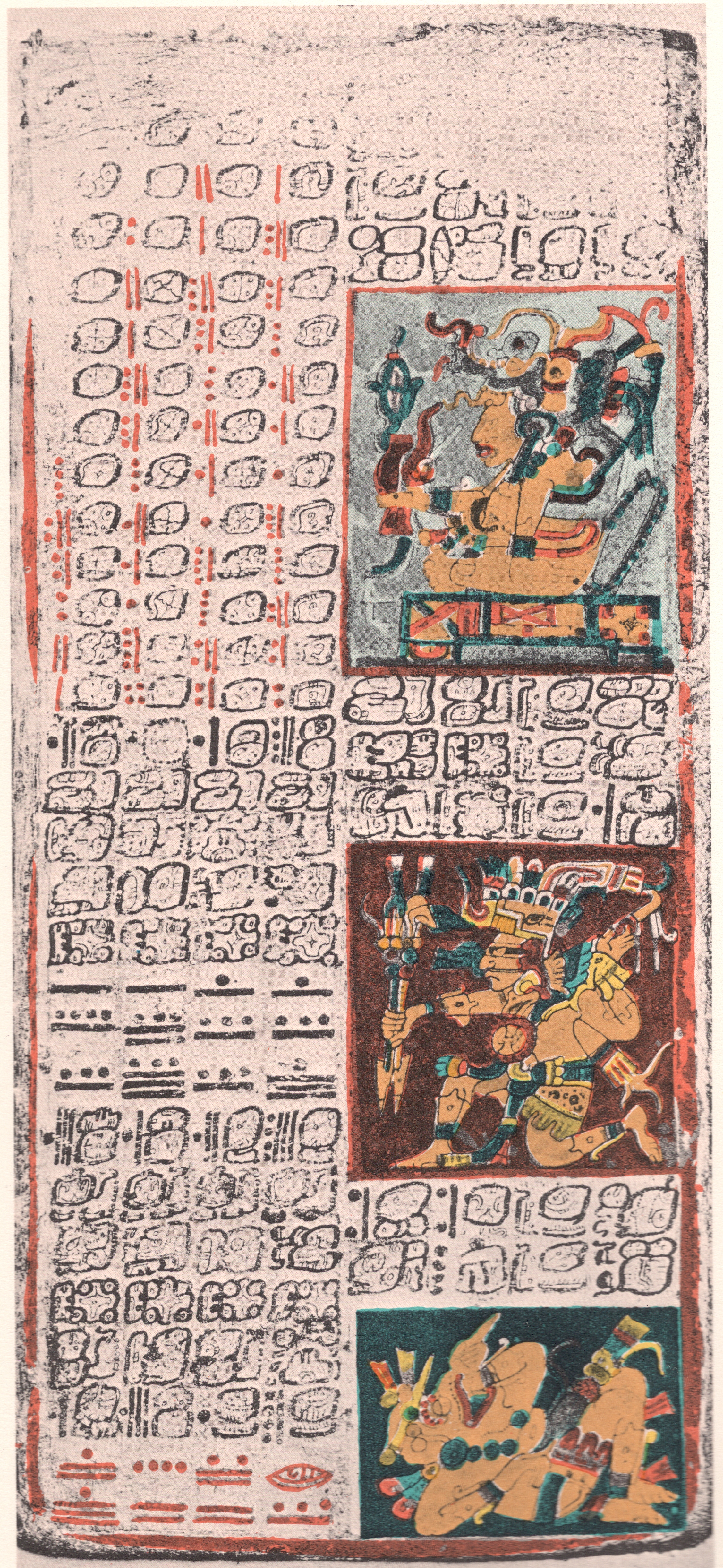

One part of the Paris Codex consists of a series of scenes where one figure is on foot, on the left-hand side, and another is on a throne on the right-hand side. The figures are surrounded by glyphs. Some of the glyphs refer to days and numbers. This series of images is a calendar of sorts: the seated figures represent the katuns, periods of 20 years. Certain prophecies were associated with each time period: as the Maya believed that time was cyclical, what had happened in the past could be used to predict the figure. The flip side of the Paris Codex covers a variety of topics. There is

a cyclical calendar dedicated to Chaac, God of Rain, and another calendar that marks the beginning of 365-day solar years for a 52 year period. Two battered pages at the end show some animals: it may be a sort of Maya zodiac.

Bruce Love, Director of Archaeological Research at the University of California Riverside, has done an exhaustive study of the Paris Codex. He believes it was a “handbook” for Maya priests, helping them interpret the interactions between celestial objects, gods, mankind and the calendar. The Paris Codex is therefore a priceless tool for understanding Maya culture and religion.

The Madrid Codex:

Scenes connected to the hunt, Madrid Codex

The Madrid Codex, also known as the Tro-Cortesianus Codex, is one of only four remaining books or “codices” attributed to the Ancient Maya culture. The codex consists of 112 pages of glyphs which were not translated until relatively recently. The Madrid Codex describes calendars, rituals and daily activities among the Maya. The original is located in Madrid.

Maya Writing:

To the untrained eye, the writing in the codex looks like a series of doodles and pictures. There are animals that look like dragons and fierce people or gods. But the

Maya language was much more sophisticated than it appears at first glance. Maya glyphs represented either a complete word or a syllable. They also had advanced mathematics and numbers appear frequently. By comparing the Maya codices and other surviving Maya writings - such as stonecarvings on temples or decorations on pottery - researchers have been able to mostly decipher the Maya language.

The Codex:

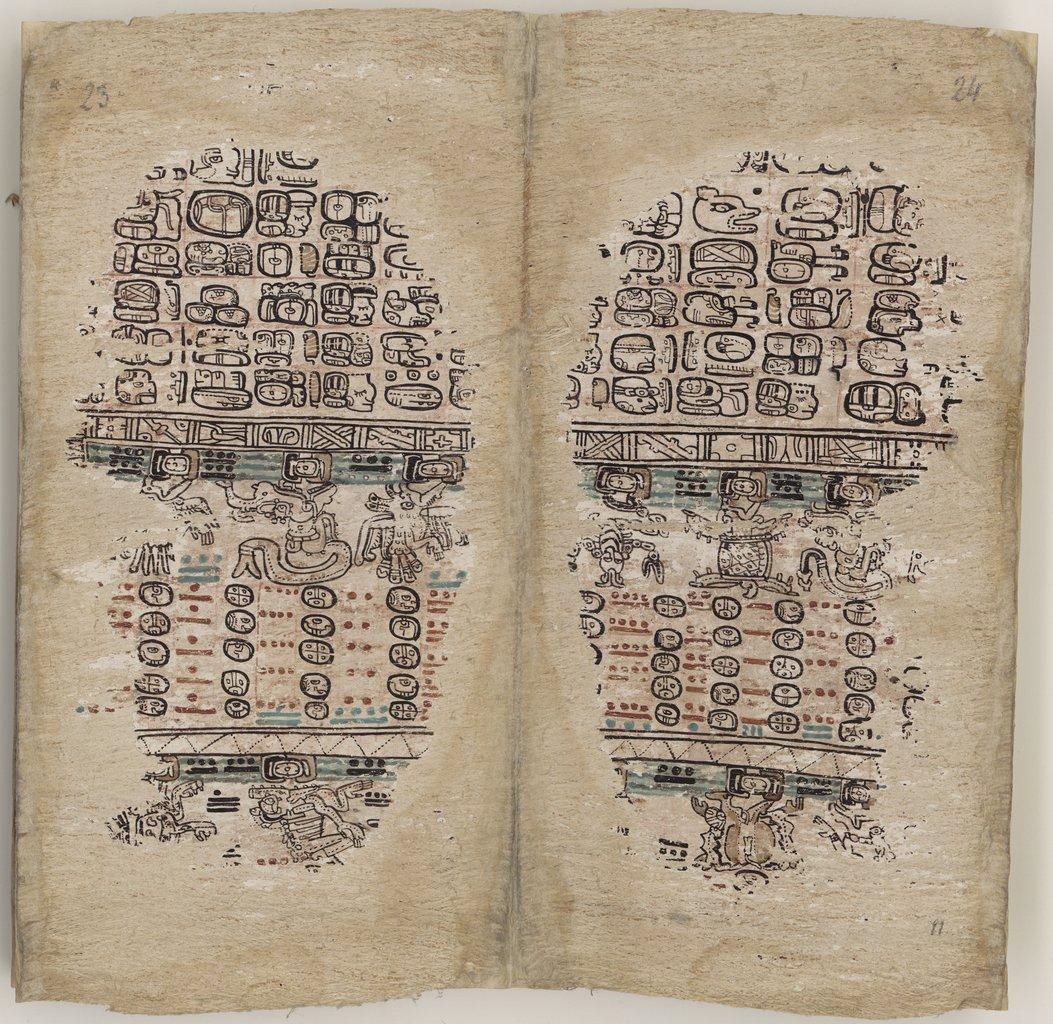

The largest of the four surviving Maya codices, the Madrid Codex is 112 pages long (56 double-sided pages). It was painted on a special bark used by the Maya especially for their books. It was once one long folio, which folded out accordion-style, but has since been broken in two. The codex is 23.2 cm high by 12.2 cm wide. Many of the colors have faded over the centuries, but there are still some reds, blues and brownish yellows that remain fairly vibrant.

Origin of the Madrid Codex:

The Madrid Codex, like the other surviving Maya codices, likely dates from the late postclassic Period, or sometime around 1200-1400 A.D. It probably was created in the Yucatán peninsula. The language represented in the codex corresponds to that of Yucatecan Maya dialects. Previously, some thought it might have been created further south, near Tikal in Guatemala, but a comparison of the images in the codex with others found in the Yucatan seems to support the hypothesis that it was created in the northern part of the Maya lands.

History of the Madrid Codex:

The codex somehow miraculously survived the burnings of Maya books organized by priests during the conquest and colonial eras. It made its way to Europe but no one knows how or when. One of its owners believed that it was sent to Spain by

Hernán Cortés: he thought so because he purchased it in Extremadura, birthplace of Cortés. At some point during its travels it was broken in two, and for a long time the two halves were believed to be separate codices. In 1880 it was proven that the two codicies, at that time called the Troano Codex and the Cortesian Codex, were in fact the same one. The two halves have since been reunited and are located at the Museum of America in Madrid.

Content of the Codex:

The codex contains descriptions of the

Maya calendars and the rituals associated with different dates and seasons. These are interspersed with images of scenes of daily life, such as weaving, hunting, beekeeping, war and even human sacrifice. There is a section on the rituals associated with the end of the 365 day solar year and the beginning of the following year. Other sections deal with the layout of the Cosmos, the gods associated with the different cardinal directions and offerings to be given to each of them. It also shows the movement of celestial bodies considered divine, such as the sun and moon. Like the Paris Codex and the Dresden Codex, the dates in the Madrid Codex are in the 260-day tzolkin calendar.

Importance of the Madrid Codex:

Because it is one of only a handful of surviving documents produced by the Ancient Maya, the Madrid Codex is a priceless document. Many aspects of Maya culture are still a mystery to modern historians, and the codices contain much information not found elsewhere. The codices in general shed light on the religious and spiritual life of the Maya and were of use to their priests and

astronomers.

The Grolier Codex:

Grolier Codex is one of the four currently known codices that survived the climate and the invaders from Spain. More controversial than the other three -- the Madrid, Dresden and Paris codices -- the Grolier Codex's authenticity has been a matter of debate.

The codex, although displaying Mixtec stylistic influence, is judged to be Maya (if genuine) based upon the use of bark paper instead of the deerhide preferred for Mixtec codices and because of the presence of Maya day signs and numbering.

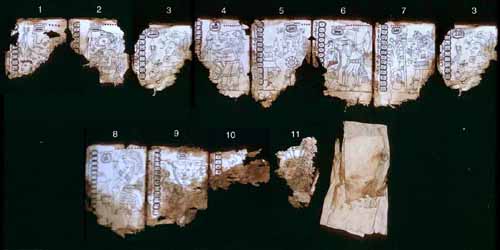

The codex is poorly preserved; the surviving page fragments display a number of figures in central Mexican style, combined with Maya numbering and day glyphs. The document is currently held by the Museo Nacional de Antropología in Mexico city and is not on public display. The physics institute of the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México subjected the codex to non-destructive testing in an effort to determine its authenticity. The results were published in 2007 and were mixed; the document apparently contains genuine pre-Columbian materials but certain aspects, such as seemingly artificially induced wear and tear, are suspect. The researchers concluded that they were unable to prove or disprove the pre-Columbian nature of the codex.

History

The Grolier codex's origin is unclear. It may have been found in the southern region of Mexico-- possibly in the state of Chiapas in a cave somewhere near Tortuguero. It is possible that it was uncovered by looters.

In 1965 it ended up in a Mexico City flea market where someone bought it. The person who bought the codex, a collector, gave it to the Grolier Club so the club could use it in an art exhibition in 1971. Later, in 1973 the Maya specialist Michael D. Coe published a catalog of this exhibition. The claimed discovery of the Grolier Codex would make it the only pre-Columbian codex discovered in the course of the 20th century, except for some codex fragments excavated by archaeologists. Now the Grolier Codex is part of Mexico's Biblioteca Nacional de Antropología e Historia (in Mexico City).

Controversy

Whether or not this codex is real has been a matter of debate among archaeologists, partly because of the its untrustworthy origin. Two notable archaeologists in the debate include J. Eric Thompson and Michael D. Coe. Thompson disbelieved that the codex was real while Michael D. Coe was one of the Maya specialists who believed it was real (Coe was also the one who named the Grolier Codex).

It is now thought that the Grolier Codex is an authentic Maya codex. This is due to the codex dating from around 1230 -- give or take 130 years -- and the fact that the art style of the glyphs seems authentic. However not everyone's suspicions have been put to rest.

Contents

Like the other codices, the Grolier Codex contains information on astronomy. Specifically the Grolier Codex contains calculated intervals concerning Venus, which the ancient Maya regarded as a god. However it doesn't have any written explanation about these intervals. By comparison to the Dresden Codex, the Grolier Codex's information isn't as impressive.

Each page of the codex has been painted on one side with a standing figure facing left. Each figure holds a weapon and most grip a rope leading to a restrained captive. Colours used on the codex include hematite red, black, blue-green, a red wash and a brown wash, all upon a strong white background. The left-hand side of each page is marked by a column of day signs; where this column is complete these total thirteen in all. Each day sign is associated with a

bar-and-dot numerical coefficient.Six pages depict a figure bearing weapons and accompanied by a captive (pages 1-4, 6 and 9),two pages (5 and 8) both depict a figure hurling a dart at a temple. Page 7 of the codex shows a passive warrior standing in front of a tree. Page 11 depicts a

death god with a javelin, pointing his weapon at a water vessel containing a snail.

Page 10 is a badly damaged fragment with the subject largely obliterated. Based on the surviving portion, Michael Coe thought it depicted a standing figure wearing a waterbird headdress and bearing an

atlatl.

![]()

You need to be an initiate of Exploring Maya to add comments!